This included the possibility that the star was shrouded in so much dust that its optical/UV light was being absorbed and re-emitted. Naturally, the team considered all available possibilities to explain the sudden "disappearance" of the star. What we see in the data is consistent with this picture." All the atoms in the puffy envelope were ionized-electrons not bound to atoms-as the ejected envelope expands and cools, the electrons all become bound to the atoms again, which releases the energy to power the transient. This produces a cool, low-luminosity (compared to a supernova, about a million times the luminosity of the sun) transient that lasts about a year and is powered by the energy of recombination. This drop in the gravity of the star is enough to send a weak shock wave through the puffy envelope that sends it drifting away. When the core of the star collapses, the gravitational mass drops by a few tenths of the mass of the sun because of the energy carried away by neutrinos. This envelope is very weakly bound to the star. The star we see before the event is a red supergiant-so you have a compact core (size of ~earth) out the hydrogen burning shell, and then a huge, puffy extended envelope of mostly hydrogen that might extend out to the scale of Jupiter's orbit. "In the failed supernova/black hole formation picture of this event, the transient is driven by the failed supernova. Kochanek, the lead author of the group's paper – – told Universe Today via email: In the end, this information was all consistent with the failed supernovae-black hole model. This was consistent with archival data taken by the HST back in 2007.Īrtistic representation of the material around the supernova 1987A. In the 2009 images, N6946-BH1 appears as a bright, isolated star. Using information obtained with the LBT, the team noted that N6946-BH1 showed some interesting changes in its luminosity between 20 – when two separates observations were made.

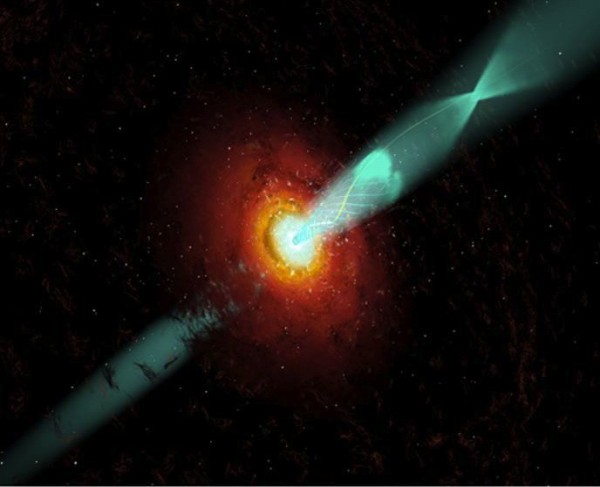

In this scenario, a very high-mass star ends its life cycle by turning into a black hole without the usual massive burst of energy happening beforehand.Īs the Ohio team noted in their study – titled " The search for failed supernovae with the Large Binocular Telescope: confirmation of a disappearing star" – this may be what happened to N6946-BH1, a red supergiant that has 25 times the mass of the sun located 20 million light-years from Earth. However, in recent years, several astronomers have speculated that in some cases, stars will experience a failed supernova. Credit: CAASTRO / Mats Björklund (Magipics) When the hydrogen fusing stops, the stellar remnant begins to cool and fade and eventually the rest of the material condenses to form a black hole.Īrtist’s impression of the star in its multi-million year long and previously unobservable phase as a large, red supergiant. This is then followed by electrons reattaching themselves to hydrogen ions that have been cast off, which causes a bright flareup to occur. This begins when the star has exhausted its supply of fuel and then undergoes a sudden loss of mass, where the outer shell of the star is shed, leaving behind a remnant neutron star. To break the formation process of black holes down, according to our current understanding of the life cycles of stars, a black hole forms after a very high-mass star experiences a supernova.

#Formation of blackhole series

Using images taken by the Large Binocular Telescope (LBT) and Hubble Space Telescope (HST), he and his colleagues conducted a series of observations of a red supergiant star named N6946-BH1. The research team was led by Christopher Kochanek, a Professor of Astronomy and an Eminent Scholar at Ohio State. And according to a recent study by a team of researchers from Ohio State University in Columbus, we may have finally done just that. And why not? Being able to witness the formation of black hole would not only be an amazing event, it would also lead to a treasure trove of scientific discoveries.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)